Nina Whittaker is the rare materials cataloguer at State Library Victoria, having previously worked as cataloguing librarian at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum. Their ancestors are from southern Japan, and Western Europe via Taranaki, Aotearoa.

I acknowledge the land I live on as Wurundjeri land. Ngā mihi, ngā mihi, ngā mihi: I pay respect to Wurundjeri Elders past and present.

The TK: Seasonal label protects Indigenous knowledge that moves with the seasons, and with it I pay respects to Indigenous peoples in Victoria, Australia and around the world as spring and autumn arrive.

A book may be a mirror to the world, but it is also a mirror to power. When we catalogue a book, we’re reflecting the conditions of power when it was created.

The broader dataset created from this cataloguing also reflects the conditions of power when the book was catalogued. While we focus on cataloguing one book at a time, this collective dataset over represents those in power, and silences those who are not.

Every day, cataloguers around the world create hundreds of thousands of data points. These represent hundreds of thousands of opportunities for change. We can transform our everyday practices to produce reparative and equity-based data.

What is equity analysis?

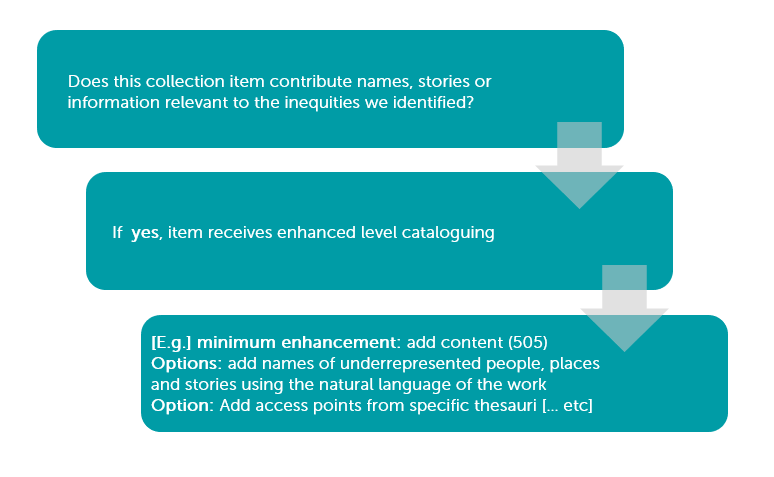

I have drawn the term equity analysis from the everyday cataloguing practice of subject analysis. In subject analysis, cataloguers flick through a resource and think about which subjects provide the best access. I hope that equity analysis can be a similar, everyday task where cataloguers briefly look through each item and add equity-based access points.

Equity analysis allows cataloguers to prioritise items which contain information that is currently unequally represented. These items go through an enhanced cataloguing procedure – which could be as simple as adding in one, two, or three extra fields.

Using equity analysis in cataloguing, we:

- Identify areas of inequity within all functions of the library catalogue;

- Understand the processes that create or maintain these inequities;

- Address these processes using enhanced cataloguing.

Equity analysis will look different in every organisation depending on their collections, communities, and context. Anyone who catalogues can practise equity analysis, and it can be scaled to factor in resourcing.

- Identify

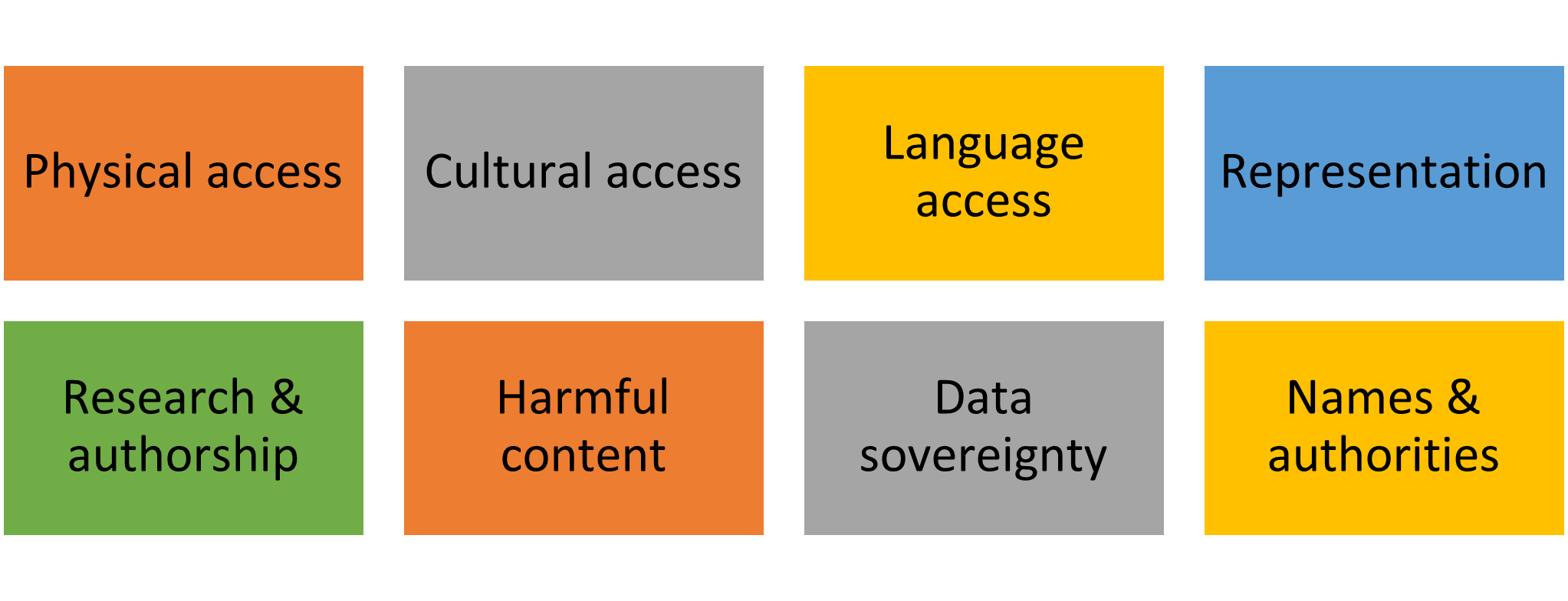

The first step is to work as a team to figure out different areas of inequity within your library catalogue. Are there more names of colonisers than of Indigenous people? Can different communities access your data safely? What about people who speak different languages?1

To begin with, keep it to ten or fewer key areas of inequity, and write down what these look like in your catalogue. As you get more familiar with equity analysis, you might want to add in more / specific types of inequities you want to address.2

- Understand

The second step in equity analysis involves understanding how the inequities you have identified are shaped by existing policies and procedures. Every process in every department in your organisation either contributes to, or detracts from, equitable access to knowledge.

This step is underpinned by a framework for antiracism set out by scholar Ibram X. Kendi. His model definitions help us drill down to specific actions which are causing or maintaining inequity. We might have some processes that are antiracist, but others that are racist.

An antiracist foundation empowers us to address other areas of inequity – for example transphobia or ableism - in an intersectional and proactive way.

Racial equity is when two or more racial groups are standing on approximately equal footing. Racial inequity is when two or more racial groups are not on approximately equal footing. An antiracist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial equity between racial groups.3 A racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups. There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups. - Address

Once you have identified key areas of inequity and understood the processes that lead to and maintain them, it’s time to address them in your cataloguing. This step will look different depending on the processes you’ve identified, the needs of your communities, and the amount of resourcing you have available.

I have used the contents field as an example of a minimum enhancement because it uses the natural language of the resource to create access through the voice of its creators. It also lets you include at least the free-text names of contributors who would otherwise remain invisible.

Access points from specific thesauri, a summary of the work, or added notes on taonga / treasures, ancestors, and names mentioned are also great steps. Refer to the inequities and processes you’ve identified to design enhanced cataloguing that is most effective for your particular context.

Equity analysis in action

- This 1986 Aboriginal History Programme is the story of a community – but a standard record doesn’t capture their names. The contents adds their eleven names, and addresses an inequity within the catalogue of the names of Indigenous creators and communities.

- Under ‘standard’ cataloguing, this book on traditional Tuna fishing in Tokelau would only show the ethnologist’s name. An added note has the names of the sixteen Tautai/elders who contributed their knowledge. The contents field also adds many Tokelauan language terms, addressing an inequity in language access.

- You would have never known this Auction of Rare Australiana includes information about the sale of Indigenous Pacific taonga/treasures. A simple notes field could contribute immensely to research, provenance, and perhaps even repatriation.

Final Thoughts

These enhanced records can look a bit crowded. However, I strongly believe that library catalogues don’t need to be lists of monographs anymore. They are historical datasets in their own right, able to move out into the wider digital ecosystem via search engines, APIs, linked data.

We need to be ambitious about what the next generation can do with library data. Every day we are transforming how we access and use these datasets. I have faith that future library users will find and use the data I add - through equity analysis - to create their own networks of meaning.

It’s not a catch-all solution. Cataloguers must be empowered and supported by an equity-based cataloguing policy. It calls for a broader equity infrastructure, as described by other contributors to this series - from inclusive technology (Kelly Gibbs) to Indigenous leadership (Kirsten Thorpe) and relationality (Honiana Love). This proposed model of equity analysis comes from my experience as a cataloguer. I hope it can be developed and transformed by many hands over time.

References

1 If you have strong, reciprocal relationships in place, you might want to talk to people with a variety of lived experiences. If not, you can read about different lived experiences and think about how to start those relationships.

2 A great way to identify specific inequities is through user surveys and collection audits.

3 Kendi defines policies as “the written and unwritten laws, rules, procedures, processes, regulations, and guidelines that govern people.” (2020).

Further reading

- AIATSIS. (n.d.). Pathways : Gateway to the AIATSIS Thesauri. https://thesaurus.aiatsis.gov.au/

- Akala. (2018). Natives: race and class in the ruins of empire. Two Roads.

- Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia. Anti-Racist Description Working Group. (2019). Anti-racist Description Resources. https://ocm.iccrom.org/documents/archives-black-lives-philadelphia-anti-racist-description-resources

- Bibliographical Society of Australia & New Zealand. (2021, January 29). BSANZ 2020: Nina Whittaker: cataloguing policies and antiracist work [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CrO_pqqcwuM&t=4s

- Cairns, Puawai. (2020). Decolonise or indigenise: moving towards sovereign spaces and the Māorification of New Zealand museology. Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand. https://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2020/02/10/decolonise-or-indigenise-moving-towards-sovereign-spaces-and-the-maorification-of-new-zealand-museology/

- Cataloguing Ethics Steering Committee. (2021, January). A code of ethics for catalogers. https://sites.google.com/view/cataloging-ethics/home

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Frick, Rachel L., and Merrilee Proffitt. (2022, April). Reimagine Descriptive Workflows: A Community-informed Agenda for Reparative and Inclusive Descriptive Practice. OCLC Research. https://doi.org/10.25333/wd4b-bs51

- Greenhorn, Beth. (2019). Project Naming: reconnecting Indigenous communities with their histories through archival photographs. In E. Benoit, III, and A. Eveleigh, Participatory archives: theory and practice (pp.45-58). Facet. https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783303588

- Kendi, I.X. (2019). How to be an Antiracist. One World.

- Kendi, I.X. (2020, June 8). Ibram X. Kendi defines what it means to be an antiracist. Penguin. https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2020/06/ibram-x-kendi-definition-of-antiracist

- Local Contexts. (n.d.). Grounding Indigenous Rights. https://localcontexts.org/

- Mayi Kuwayu. (n.d.). Indigenous data sovereignty principles.

- NSLA. (2022, July 28). Reimagine descriptive workflows: an Australasian perspective. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwsf3zgtjkc

- The Trans Metadata Collective, Burns, Jasmine, Cronquist, Michelle, Huang, Jackson, Murphy, Devon, Rawson, K.J., Schaefer, Beck, Simons, Jamie, Watson, Brian M., & Williams, Adrian. (2022). Metadata Best Practices for Trans and Gender Diverse Resources (1.5). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6829167

- We Here. (n.d.). https://www.wehere.space/

- Whittaker, Nina and Geraldine Warren. (2020). Let's Get Reo: the role of cataloguing in creating equitable access. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/stories/blog/2020/lets-get-reo

- The proceeds from this article have been donated by Civica to the Aboriginal Literacy Foundation.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.